Alfredo Alves Reinado

Name: Alfredo Alves Reinado

Place of origin: Maubessi

Alfredo Alves Reinando was killed in the apparent assassination attempt on President Jose Ramos Horta on 11 February 2008.

After the Indonesian invasion, Alfredo and his family fled from advancing attacks. In 1978, at only 12 years of age, he was forced to work as a helper, TBO, for a soldier from Sulawesi. As a TBO he witnessed many military offensives.

At the end of the soldier’s tour of duty, he took Alfredo, against his wishes, to South East Sulawesi. Alfredo was sent to school, but the soldier and members of his family often mistreated him. On one occasion after being severely mistreated, Alfredo ran away by bus and then boat to Kalimantan. He worked there for several years until 1986 when he was able to take a boat back to East Timor. He was 19 years of age.

In Dili Alfredo joined the clandestine movement and in 1995 led a boatload of East Timorese refugees to Australia. In Australia he worked in the shipyards in Western Australia, and after the referendum in East Timor returned home. After 2002 he entered the East Timorese military and was appointed commander of the Naval Unit. However, in July 2005 he was demoted because of misconduct and assigned to the military police. In 2006 he deserted to join a group of rebel soldiers who earlier had deserted, and in May 2006 was involved in an attack on Dili. Then followed manhunts, capture, escape from jail and further raids, until he was killed in February 2008, in circumstances which have still not been established.

See the article by Sara Niner: Major Alfredo Alves Reinado: Cycles of torture, pain, violence.

He gave the following interview to Helene van Klinken at the Hera Naval Base, Dili, 5 March 2004.

- Fleeing Indonesian attacks

- Capture and recruitment as a TBO

- Abducted

- Life in Sulawesi

- Escape

- The Commander’s letter

- Another escape

Fleeing Indonesian attacks

‘I was born in 1966. Before 1975, my family lived with my Portuguese grandparents who came to East Timor when my father was about twelve years old.

When the fighting between the political parties broke out in 1974, we all fled to Maubessi. We stayed there until the Indonesians moved into the area; then we fled further south to the area around Turiscai. We stayed there for several months. Towards the end of 1978, at the time when the Fretilin leader Nicolau Lobato was killed, the Indonesians suddenly began shelling and bombarding us with rockets. We ran away, just anywhere. I became separated from the other members of my family and followed a group of people that I didn’t know.

When we were running we would often see dead people. Death was everywhere. The smell of dead bodies, it didn’t go away. And the noise of people crying because they are hungry—you can’t forget that. We were lucky if we could eat twice a day. We fried corn then made a powder from it. We kept it in one of those square biscuit tins. We would eat just a little bit. Everyone was very skinny. People died of fever, that was the most common.We were scared of the Indonesians but also the Fretilin leaders. They also killed people who did not agree with them. They took some people away and we never saw them again.

Finally, we made our way to Fatubola in Maubessi. There I found my mother and grandmother and my younger sisters. Then they decided to surrender to the Indonesians. However, they were worried about me surrendering as they had heard stories that young men would be killed. So they introduced me to another family and left me with them. As Fretilin didn’t want people to surrender at that time they had to do this secretly and in small groups.

I stayed with the family that my mother introduced me to. We moved all the time, never long in one place. I had to look for my own food. One day I went with a friend to search for food. We wandered a long way from our camp, into an Indonesian controlled area. Suddenly machine guns were firing at us. We started running in different directions and got separated. A bullet grazed the side of my head and sheared off a bunch of hair. I had long hair at that time and I wondered why the side of my head felt hot.

Suddenly I saw a young East Timorese carrying a bamboo pole. Later I learnt he was a soldier’s helper, TBO, collecting water in the bamboo pole for the Indonesian soldiers at the Fatubolo camp. I called out to him, but he was scared and ran away. I followed him; wherever he went I followed. I followed him right into the Indonesian military camp, until I stopped, confronted by guns pointing at me from all directions. I was very surprised. I was about 12 years old then.

Capture and recruitment as a TBO

Indonesian soldiers crowded all around me. I didn’t know what they were saying, though I was not scared. There were many East Timorese children in the Indonesian camp. They translated for me what the soldiers were saying. The soldiers asked me lots of questions. I can’t remember everything they asked, and I didn’t know how to answer. They kept asking if I was alone. Then they cut my hair. They laughed because one side was short (from the bullet). They gave me new clothes to change into. I felt like I was a prisoner.

A few days later several East Timorese civil guards working for the Indonesians, Hansip, arrived on horseback with supplies and rice for the soldiers. One of them recognised me. He told the Indonesian soldiers that my family was in Maubessi and asked if he could take me there. There was a long serious talk among the soldiers, but eventually the soldiers agreed I could go to Maubessi.

So my relative took me back to the camp in Maubessi where the Indonesian military held people who were captured or had surrendered. I found my mother, grandmother and sisters there; they had all survived. We had some corn and beans from the International Committee of the Red Cross, ICRC. A battalion from Sumatra was in charge in Maubessi at that time; but soon after I arrived battalion 725 from Sulawesi took over from them.

My sister was already attending school, which was run by Indonesian police. They recruited several former East Timorese teachers to teach there. The soldiers taught them Indonesian language, then they had to teach the students. About one week after arriving in Maubessi, I was playing in the school yard—I had not yet registered for school— when a soldier, Sergeant T, came into the school and called me using my name. He told me to go with him to the soldiers’ post. He was preparing to join an operation and gave me a rucksack with rice and other supplies to carry. My mother was upset that the soldiers planned to take me away and came to the post to protest. The soldier told her that after I finished this operation I could go back home.

I had to take supplies from Maubessi to another area near Fatubolo. It is not very far, you can see it from Maubessi, but it takes about four hours to walk and is very rugged. I felt sad and worried. I had just returned home and now I had to go away again. But I couldn’t do anything about it.

A platoon of 30 soldiers had about 10?15 TBOs—approximately one TBO for two soldiers. There could not be too many as we moved around all the time and there would be no place to sleep. We were servants and had to work for the soldiers who recruited us. We had to collect water, cook, and wash the dishes. We went with soldiers on operations. We were porters and sometimes had to carry heavy loads. On my first operation I remember we were attacked by the Fretilin guerrillas. I had to lie behind my soldier, Sergeant T, and reload the magazine for his gun. I was scared. The shooting went on for about half an hour and we went through six magazines. No one was killed in this operation. One Indonesian soldier got hit in the head and another soldier got a leg injury from a bamboo stake set up by the guerrillas as a trap.

On one patrol we came across a group of people. The soldiers shot them all, but they spared one little girl called Amelia, who was about two years old. She was half Portuguese and very pretty. A soldier from our platoon looked after her and carried her.

Read more about the conditions and treatment of Alfredo and other TBOs in the CAVR report: 7.8.2.1, Nos.70-80.

Abducted

In February or March 1980 we got to Aileu, and the soldiers began cleaning their equipment because they were going home to Sulawesi. Some of the TBOs were sent home, and older TBOs were sent on new military operations. But the soldiers took a group of TBOs, including me, in the truck which came to take them to Taibessi, the military base in Dili. They never said anything to me about why they took me with them.

The soldiers from our platoon took seven children with them to Dili. Most of them were TBOs except Amelia who was spared when her parents were killed, and also Afonso. Afonso was about my age. He came from a camp where captured East Timorese were held, south of Baucau. When our patrol passed through the camp, a soldier asked his parents if he could take Afonso with him. We stayed in Taibessi for about one week. We didn’t have jobs, we just played together. But I wanted to go back to my mother in Maubessi.

One day the battalion was on parade and we heard the military police tell the soldiers that they were not allowed to take children with them to Sulawesi. After that the soldiers immediately began packing up to leave. Sergeant T said that I could come to the port to see them leave. However, he told me that I couldn’t just go in the car. If the military police found me they would not let me into the port area. He said I had to hide in a box. I was surprised, but I wanted to see the big ship.

Sergeant T put me in a big box. I wasn’t really scared but I felt quite alone. I could see out of the box a bit and I could hear them talking around me. I felt myself being lifted onto the truck, and then later carried some more. After some time I tried to get out of the box. But Sergeant T told me to stay hiding because the military police were coming. Then I heard the siren of the ship, it was very noisy and suddenly I could feel the boat moving. After about 20?30 minutes in the box I felt very hot and sweaty; but finally T told me I could get out. I saw we were on a big boat and the other children from of our group of seven were also there. They all said that their soldiers brought them onto the boat in a box. We looked around and could see that Dili was far away, and that we were moving away from the shore. I don’t know how the others felt, but I felt very sad and was crying. I thought about my mother in Maubessi, and I thought that I would never have a chance to go back there. I hadn’t seen her since I was taken from the school grounds.

I saw many other children on the boat, though I don’t know how many. Some of the children were crying. Most of us couldn’t do anything because we were so sea sick. But we didn’t have to hide any more. After about one week we arrived in Kendari in South East Sulawesi. We stopped in the barracks for one week. It was a great culture shock. It was such a different life there.

Life in Sulawesi

Sergeant T took me to his parent’s place in Lamikonga village in Kolaka sub-district, Kendari. He asked me to call him “father.” I was separated from most of the other children who went to different places in South East Sulawesi with their soldiers.

For the first month, T’s family looked after me well and they paid for me to go to school. But then things started to change. Sergeant T’s mother was good to me, but his sister and the rest of his family didn’t like me and often hit me. They treated me like a slave. Every morning I got up at six o’clock. I had to fill the water containers in the house from the well. The well was not too far away, but the house was tall and the buckets of water had to be carried up a long flight of stairs. I had to prepare food for the 40 ducks they kept and collect the eggs. I would then bathe and have breakfast. School started at 7:30am but it was very close to our house, so I could arrive on time. In the afternoon I had to fill the tanks again. I had to do this every single day. I also had to go and help in the rice fields.

After two years T got married and he asked me to live with him. His wife was very good to me; she did not make me work so hard and treated me like family. I always felt secure round her. She was happy when I called her “Mum.” Occasionally she gave me money without telling her husband. She had a younger brother about my age, so perhaps I reminded her of him. Sometimes I had to do the cooking. One day I was frying fish when the hot oil tipped over my legs. I still have a scar. I couldn’t go to school for three months. Then things changed for my adoptive father, and he decided to send me back to his parent’s house. It was just like before, and I was treated as a slave. During holidays I had to work long hours in the rice fields and help in their cinnamon plantation.

But I worked hard at school and did well. I finished elementary school and went straight into junior high school. I didn’t have to sit for the usual test. I did well at school and the teachers liked me. I liked biology especially and could remember things. I won an award at school for my class. I still have the certificate.

The family asked me to become a Muslim. I couldn’t say anything; I had to do everything with them. But in my heart I thought, I know who I am and where I come from. In my village there was another East Timorese. The villagers told me about her. I saw her but was too shy to talk with her.

One day when I was about 16 years old I visited a friend and stayed overnight without telling my family. T’s sister who was about 23 years of age was in charge of the household. She was very angry with me. She made me sit squashed under a bed with a piece of wood under my knees. It was very painful and I was crying. Then her mother came and told me to get out from under the bed. She asked me things but I didn’t answer and this made her angry. She was ironing and pushed the hot iron on my arm burning me. I decided then that I would run away.

Escape

I still had contact with Afonso and Amelia. I was about 16 when Afonso and I decided to try to escape and go back to East Timor. We asked Amelia if she wanted to come with us, but she said she had no idea where would she go. Her parents were dead and she didn’t know anything about her family. Afonso and I went to the harbour and hid on a ferry heading for Ujung Pandang. However, Afonso’s soldier came looking for him and found us. Afonso is still there in Kendari. I often think about him and Amelia and would like to go back there and help them come home.

T took me back to his house. He tired me up and beat and kicked me. His wife was crying, but she couldn’t stop him. He used to beat her too. I was black and bruised from the beating. I was also angry and it made me try harder to escape.

I talked to another soldier I knew and told him I was going to run away. He must have told T about this. T told me he would kill me if I tried to escape. He beat me till my face was black and swollen. That night, with my terrible, swollen face and just the clothes I was wearing I crept out of the house. I walked across the paddy fields about three kilometers to the town. It was after midnight. I found a house that was under construction and I lay down on the building materials to sleep. I woke up at four o’clock and I saw T driving round looking for me. I walked another one kilometer and then caught a bus. They let me on without a ticket. Perhaps they saw that I was abused and wanted to help me. It was a six-hour drive to the town on the harbour.

There were no boats from this port to East Timor. Some people felt sorry for me. I still had my black, swollen face and they let me come on their boat going to Samarinda in Kalimantan. I worked in the kitchen to pay for my trip. It was the first time I learnt how people lived on boats. I made friends on the boat and when we arrived they introduced me to people who let me stay with them. I worked with them in the black market. We would row out to receive electronic goods and clothing from the boats before they arrived in the harbor. We smuggled them in to avoid paying tax, then we could sell them cheaply. I had nice clothes and a watch.

But I decided I wanted to go back to school to finish junior high school. So I found another job in a vegetable shop, which imported vegetables from all over Indonesia for the big mining companies in Kalimantan. I began work early in the morning so I couldn’t go to the regular school. I enrolled in a private school and attended school in the afternoon. It cost Rp5,000 per month, which was quite expensive. I liked to go down to the harbour to help collect the vegetables; a lot came from Surabaya. I got to know some of the people on the boats who brought the vegetables and I heard from them that there were boats in Surabaya that went to East Timor. I was in Samarinda for nearly two years, till I was nearly 19 years old. I felt okay about living there because I was independent.

One day, just after I had finished junior high school, I heard that there was a boat leaving for Surabaya. I decided I would leave on this boat. I had not received my certificate, but I didn’t care. All I had was the clothes I was wearing and my day’s wages in my pocket. The people knew me so they allowed me to work on the boat to pay my way. It took four nights to get to Surabaya. When I arrived I stayed in the port and slept on our boat, while I looked for a boat leaving for East Timor. I heard there were lots of thieves so I kept my wallet in my underwear, though I didn’t have much money.

After four days I was discovered by the customs officers. When they checked our boat they found me in the kitchen. I had no identification papers. They took me into Surabaya and asked a lot of questions. I told them I was from Samarinda and wanted to go to East Timor to get a job. I didn’t tell them I was East Timorese. I was really afraid they might send me back to Sergeant T in Sulawesi, but they let me go. However, I had no success finding a boat and my money was nearly gone.

The Commander’s letter

I decided that the only thing I could do was to go to meet the military commander and ask for his help. I found the headquarters of the Surabaya military command (Kodam). I had learnt how to approach soldiers. I said I needed to talk personally with the commander. He was away for two days, but I kept coming back. When he arrived I was already waiting and he signaled to me. I told him I had something important to tell him and he invited me in. Before I said anything, I told him I needed his help. Then I told him my whole story. He told me to come back later. Then he gave me dinner and a letter he had signed.

I returned to the port. When the port officials and police saw this letter, they became busy looking after me. They arranged a ticket on a boat. The captain was very nice to me. The crew members also were good to me, and I helped them. They saw that I was good working with boats and told me if I couldn’t get a job in East Timor I could get a job on the boat. After four days and five nights we arrived in Dili. It was 1986 and I was 19 years old. It was a Saturday – I still remember.

But we had to wait three days off shore because the harbour was so busy. Finally we came into port. I grabbed my bag and jumped ashore. I was so happy to see Dili again. But it had changed so much in six years. My friends on the boat said to me, “Where are you going with your bag, you’d better leave it here.” But I just said, “I know where I’m going.”

The first thing I did was to look for transport to Maubessi. That took me one day. But then I found I needed a letter of permission to travel (surat jalan). But then I thought, I have one, and produced the letter from the commander in Surabaya. Well, you should have seen how people reacted when they saw the letter. “Where did you get that?” they asked. They were so surprised, and then they really looked after me.

When I got to Maubessi, I went straight to my mother’s house, but different people were living there. I had trouble talking with people because I couldn’t speak Tetun. People just looked at me strangely. I felt very sad. I went down to the market. I saw an uncle, but he did not recognise me. Suddenly, someone called out to me, “I’m Thomas, your friend, don’t you remember me?” He told me where my mother was living. I was so happy I had found someone who knew me and I now I knew where my mother was. She was so surprised to meet me because she thought I was dead. Every year she used to put out flowers for me in the ceremony for the dead. But I couldn’t talk with her. She didn’t know Indonesian and I didn’t know Tetun. Thomas had to translate for us. I was introduced to all the family. My mother had a brother in Dili, and they suggested I should try to get work with him.

I went back to Dili and found my uncle’s house. I could understand them talking a bit. They were saying, “He says his name is Alfredo.” They said, “Well, there’s an Alfredo who is the son of so and so, and an Alfredo the son of another relative. Oh yes, and there’s the Alfredo who was taken to Indonesia.” When I heard them say this, I jumped up and said, “That’s me.” They all crowded round and hugged me. They said my father had tried to send letters. They all thought I was dead. My uncle invited me to work in his logging business. I did that for a while, then I became a driver and I learnt to speak Tetun.

Another escape

In 1987 I joined the clandestine movement. I did lots of missions for them. I loved to go sailing in the harbour. Because I was good with boats they gave me a task to damage some Indonesian boats in the harbour. Yes, I was naughty in the sea, but they were my orders. In 1995 I was given the task to take a group of 18 East Timorese to Australia by boat. We were the first (and only) group of East Timorese to arrive in Australia by boat. Another boat tried to reach Australia but they were captured before leaving East Timor.’

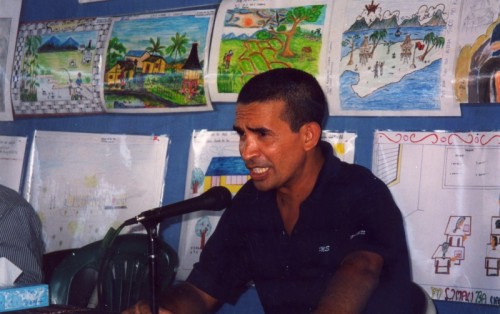

Alfredo Alves Reinado, left, CAVR public hearing ‘Children and conflict,’ Dili, 29-30 March 2004. Rev Agustinho de Vasconselos, CAVR National Commissioner, with Bible (Photo: Helene van Klinken)

Alfredo Alves Reinado, CAVR public hearing ‘Children and conflict,’ Dili, 29-30 March 2004 (Photo: Helene van Klinken)