The Seroja Institution, Panti Asuhan Seroja, was housed in a Portuguese-era building in Bario Formosa, Dili. During the few months when Fretilin controlled the territory from September 1975, it was used as an orphanage, orfanato in Portuguese. In late 1975 some of the children living there were members of the Conceição family. Their parents were UDT supporters who had been killed by Fretilin during the interparty conflict. When the Indonesian military attacked on 7 December 1975, all the children from the orfanato fled with their carers to the district hospital in the foothills south of Dili. Several weeks later the Indonesian soldiers cleared the hospital. They identified the children as victims of Fretilin and sent them back to the orfanato.

On 1 April 1976 Seroja Institution was officially opened. Until 1978 it was run by the Indonesian military, and soldiers were often involved in the day to day running of the institution. Besides delivering food and other supplies, soldiers taught the children about integration and to sing nationalistic songs. It received funding from Suharto’s Dharmais Foundation and was named for Indonesia’s Seroja military campaign to annex East Timor. At that time thirteen Conceição children were living there, together with another thirteen children. Some of the other children may have been hospitalised at the time of the invasion; they were unable to return home and became separated from their families.

The staff of the orfanato who had been employed by Fretilin were not reemployed by the military. Instead, soldiers employed several women whose husbands were Apodeti and UDT leaders killed by Fretilin soon after the invasion. The institution was a powerful symbol for the military in furthering its version of the history of ‘integration’ for several reasons. It bore the name of the Indonesian military campaign to subjugate East Timor. At least half of its first occupants were the orphaned Conceição children whose parents were killed by Fretilin, and it was run by female staff who were widowed after their husbands were also killed by Fretilin.

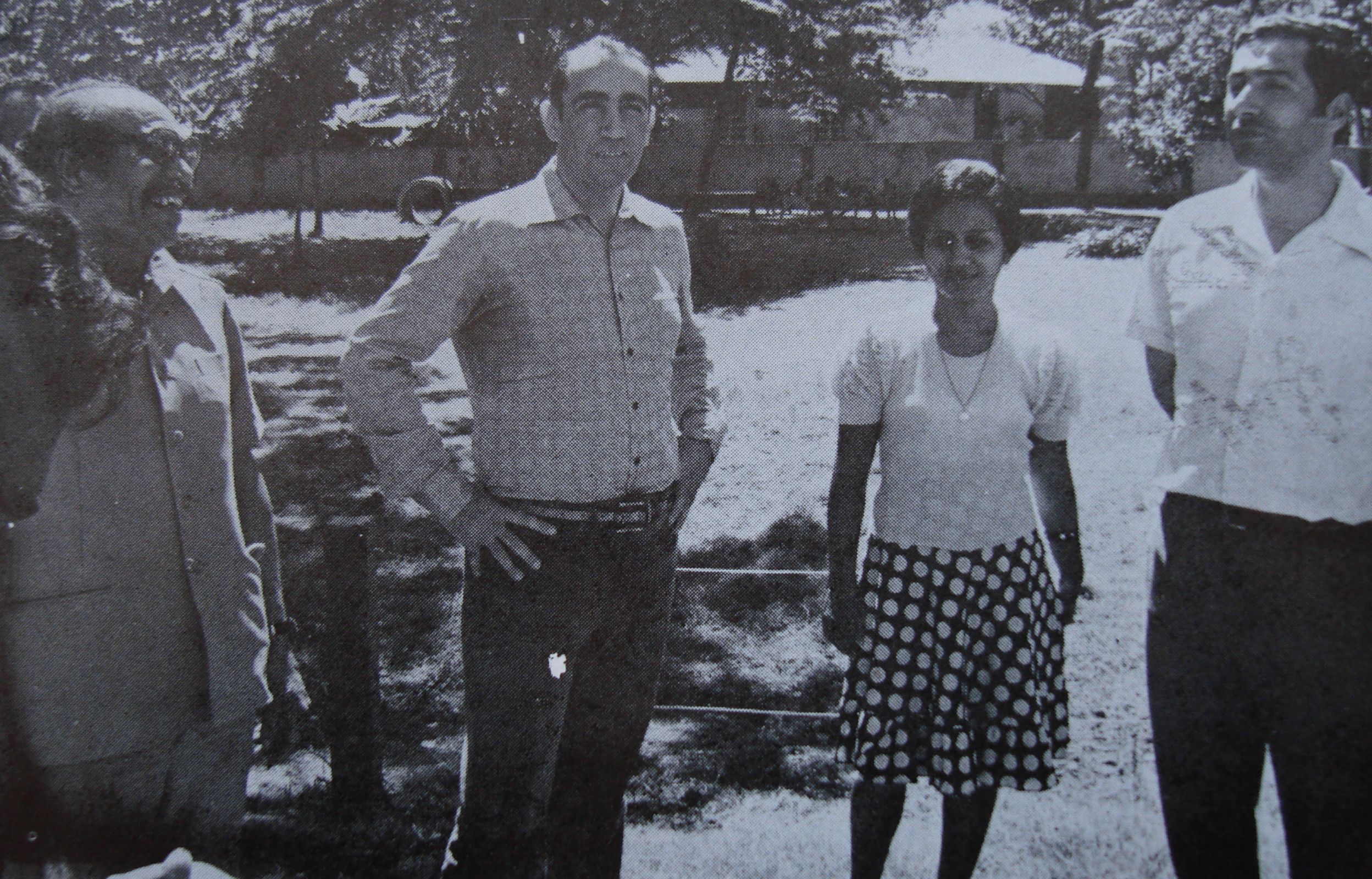

In June 1976, soldiers took the Portuguese General Morais da Silva, in Dili to negotiate the release of twenty-three Portuguese prisoners, to this symbolic institution as part of its efforts to convince him that Portugal should support integration.

The Portuguese General Morais da Silva visiting Seroja institution, June 1976; Arnando dos Reis Araujo, the governor of East Timor, is on the left (Soekanto 1976)

Often soldiers brought children separated from their parents to Seroja after a military campaign. Many of these soldiers later returned to collect a child at the end of their tours of duty and took them home to Indonesia. Maria Margarida Babo, a staff member at Seroja for the entire period of its operation until 1999, remembers soldiers bringing groups of children by helicopter from the districts to Seroja. Some of these children were reunited with their parents and family members who came to the institution in search of them. Staff members were often unable to help families in their search as some children were too young to provide information and the soldiers who delivered the children there gave the staff few details. The staff could not speak Indonesian well and were usually afraid to demand explanations from the military personnel in charge of the institution. Maria Margarida Babo tried to keep her own records of the movement of children. Unfortunately her notebooks were destroyed in the forced evacuation in 1999 when the institution was burnt down.

When the Department of Social Welfare took over control of Seroja institution in 1978, it specifically prohibited the adoption of children living in the institution by soldiers. Nevertheless, staff members remember children being taken away by soldiers or soldiers’ wives. One such child was two-year-old Thomas who was taken in 1982 or 1983. A group of women from the association of soldiers’ wives ( Persit) used its influence with senior military officers to obtain a letter of permission from the Department of Social Welfare to adopt Thomas. However, after several years, the practice of soldiers irregularly removing children from Seroja stopped.